Blog

A silly debate? Leandro Prados de la Escosura’s contribution to the ‘beyond GDP’ debate

Review of Leandro Prados de la Escosura, Human Development and the Path to Freedom. 1870 to the Present. Cambridge UP, 2022.

The notion that GDP is an imperfect guide to well-being is arguably as old as the concept itself. Its limitations were for example already discussed in detail by Simon Kuznets, and these issues were a part of the debate in the 1940s between Richard Stone, Milton Gilbert and Kuznets about the exact measurement of National Income. There has since been an undercurrent of literature trying to compensate for the flaws of the official System of National Accounts, for example by incorporating inequality, or environmental problems, or health and education into the measured concepts. The Human Development Index, inspired by the welfare-theoretical work by Amartya Sen and developed by UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) is the best-known example of this new approach. Since the financial crisis of 2008, however, and the report by Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi (2018) the well-being debate has both broadened and deepened, and increasingly has had an impact on economic history. The core ideas are simple: firstly, the ultimate goal of economic development is not just an increased command over resources (as is measured by GDP), but the increase in overall wellbeing of the relevant population. Secondly, wellbeing is multidimensional – we do not live by bread alone, and health, political rights, education, a healthy environment, inequality etc. are also important dimensions that have to be taken into account when the ‘achievements’ of economies are assessed. However, it is not straightforward to interpret, sometimes very different, trends in the various concepts at the same time. One way to do this, is to aggregate the different dimensions into a single, composite index. But for a concept that has many dimensions, this is not an easy task. That we are interested in something multidimensional but that we would like to measure it by one single index, has led to the proliferation of attempts to solve this puzzle.

Economic historians have traditionally also struggled with these issues. The British Standard of Living Debate (when did British labourers start to profit from industrialization and growth?), the American ‘Ante-bellum growth puzzle’, the literature on the increase in wellbeing during the Interwar period, are examples of debates in which various indices of wellbeing and growth developed differently over time, questioning the use of ‘traditional’ measures such as real wages or real income. A more recent debate focuses on the period after 1980, when economic growth continued (albeit at a lower rate than before), but trends in inequality and health, suggest a stagnation in the increase of wellbeing.

Leandro Prados de la Escosura (LP), one of the leading economic historians who has published many innovative papers on European (and global) economic growth, has produced an ambitious contribution to this debate. It offers, on the basis of a rich dataset, a reinterpretation of the evolution of wellbeing in the world since 1870. He builds his new view on data about four dimensions of wellbeing: life expectancy, education, GDP per capita, and liberal democracy, the latter being an index of the quality of political institutions (and therefore the degree of political freedom). It leads to other insights into long term development of wellbeing. An important example of this new view is that between 1920 and 1950 wellbeing increased much more than the increase of GDP per capita suggests, because literacy and education continued to grow at a robust rate.

A researcher wishing to go beyond GDP and measure multidimensional wellbeing in the past, has to make a number of choices to get to a composite wellbeing index that charts the long-term trend. Firstly, how many and which dimensions to include (a question I return to below). Secondly, how to transform the series of the individual dimensions to make them comparable with each other – how to standardize series with very different scale. And thirdly, how to aggregate the various series. I will start with the second issue, as part of the innovation that is offered by LP relates to this. The problem is as follows: series for life expectancy, education, GDP per capita and democracy measure concepts with very different scales. GDP per capita at the world level increased by a factor 10 between 1870 and 2020 (from about 800 dollars in 1990 prices in 1870 to 8000 dollars in 2020). Life expectancy more than doubled – from 27 to 70 years on a global level –, years of education increased from 1,2 to 8, and the index of liberal democracy is constructed in such a way that the extremes are zero and plus 5. The fundamental difference between GDP series and the rest is that GDP grows exponentially – at a rate of on average 1,5% per year, whereas life expectancy and years of schooling (and liberal democracy) are bounded, they run up against natural limits. In Japan, for example, life expectancy is 84 years and still increasing, but at a very slow pace, because it is already so high. The same applies to years of education, which does not increase much anymore in the wealthiest countries. There is therefore a ‘natural’ tendency for the growth of wellbeing, in particular when dominated by life expectancy and education as in the Human Development Index, to slow down beyond a certain point. LP concludes from this that ‘an increase in the standard of living of a country at a higher level implies a greater achievement than would have been the case had it occurred at a lower level’ (p. 19).

LP has adressed this problem by applying a so called Kakwani transformation to the bounded series, which is, technically, a way to blow up growth at higher levels of the series, when increases in life expectancy and education are more ‘difficult’. The increase of life expectancy from say 27 years to 70 years becomes much more spectacular after being treated with Kakwani: the global average then rises from 0,027 to 0,35, or by a factor 12 (lower and upper limits of the series are 0 and 1 respectively); if it continued to 80 years the new Kakwani level becomes 0,614, or an increase by a factor 22. The rather ‘dull’ series of life expectancy suddenly becomes highly dynamic. A rise of life expectancy from 82 to 83 years has the amazing effect of increasing wellbeing from 0,74 to 0,83, or by 13%. It is not just the elderly who profit from this, the entire population sees it wellbeing exploding when life expectancy grows toward the upper limit of 85 years! Increases in education are inflated in the same way; for example, the first five years of education have the same effect on wellbeing as the increase of educational attainment from 16 to 17 years (I know university education is good, but is it that good?). An important result is that a composite wellbeing index based on these underlying series, will continue to show fast growth of wellbeing when it is getting really wealthy, but this is the result of the assumption on which the entire exercise is based that at high levels growth is more difficult and therefore should be rewarded more than growth at low levels. The post 1980 divergence between GDP growth and wellbeing, which plays such a fundamental role in the beyond GDP debate, however, largely disappears due to the Kakwani transformation.

GDP growth, on the other hand, gets compressed by LP. The log of GDP per capita is taken as the best measure of wellbeing (a not unreasonable assumption, as we tend to think about our incomes in terms of relative and not absolute changes). Moreover, for the standardization of the series a relatively high upper limit (goalpost) of 47.000 1990 dollars is chosen. The result of this is that all action takes place in the lower half of the index as only a few countries approach the high upper limit. The odd consequence of these transformations is that whereas in the real world GDP per capita in the long run increases much more than life expectancy and education, the indices – after Kakwani and log – show the opposite pattern: the average level of life expectancy and of years of education increases by 0,4% per year between 1870 and 2015, whereas income grows at only 0,1% per year, and political rights at 0,15% per year. The result, in brief, is that LP’s augmented human development index (AHDI) is largely driven by life expectancy and education.

The early 1930s clearly demonstrate where this leads to. Between 1929 and 1933, when the world economy collapses, mass unemployment peaks, democracy is on the defensive and Hitler seizes power – in short, during our worst nightmare -, the AHDI shows a remarkable increase in wellbeing, thanks to the increase in life expectancy and education, which overpower the declines in GDP per capita and liberal democracy (p. 32-34). By this standard, the world’s population was better off in 1933 than in 1929, a result that is, to say the least, challenging established views. This happy growth of wellbeing continues in the rest of the thirties (next data point is 1938), and between 1938 and 1950, the next year for which estimates are available. It explains the ‘superior’ development of wellbeing compared with GDP in the first decades of the 20th century, which is one of the main conclusions LP draws from his reconstruction.

The book presents estimates for wellbeing for key years, often per decade or per 5 year period (1933 is a bit of an exception). The story gently moves from 1938 to 1950, to 1960 and so on. There are no crises, no wars, the millions who died on the battle fields and in concentration camps, have no impact on this story – there is only the smooth increase of indices, the well-paved path to freedom. GDP series that are often available on an annual basis, show huge fluctuations: sharp depression in the 1930s, dramatic contractions as a result of the World Wars, which is at least one way to connect to the real tragic history of the 1930s and 1940s. The concepts that dominate LP’s story, life expectancy and years of schooling, move slowly in time, driven by long-term processes and grow gently. Not only are life expectancy and years of schooling relatively immobile, by focusing on the comparison of years of peace and stability, this tendency to get harmoniously growing indices is strengthened.

This brings me to the first choice made by LP: that of the dimensions included. There is no gender inequality in this study, no racism and slavery, no warfare and its brutal impact. There are no series which reflect the dark side of development such as biodiversity decline and pollution. When LP discusses inequality it is inequality between countries, not within countries. The argument for not including within country inequality is that good data are not available, yet he mentions two recent papers which have produced such datasets. The problem with the old, GDP based studies of economic development was that they were concentrating on the good news only – the worldwide growth of real incomes – but by focusing so much on two other indices which show the same happy global trends the picture does not become more nuanced (and even the 1930s become a success story).

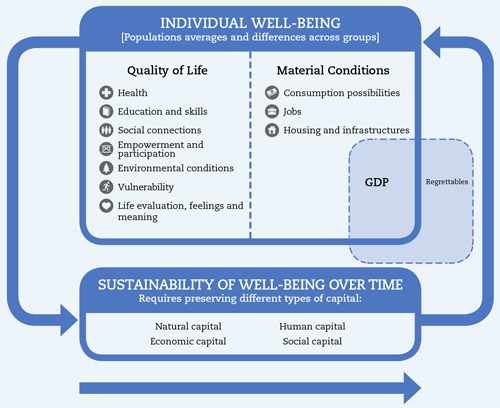

Framework How is Life?

What is needed are clear criteria about which dimensions should be included in composite indices of wellbeing, to go beyond the ad hoc choice based on subjective preferences of scholars and the availability of datasets. Sen, the intellectual grandfather of this research, is not going to produce a list of relevant dimensions – and the number of dimensions of wellbeing that are potentially relevant is endless. And the list becomes even longer when next generations are taken into account to deal with sustainability issues. In their ‘How is Life?’ studies the OECD has developed a framework for this, in which such choices are made by panels of experts (see figure 1 above. 11 dimensions are defined and measured, and via the capital accounts the issue of future generations is covered. Much more can be said about this, but it is probably the best, internationally agreed framework. This is also how it has been used in the two reports How was Life? from 2014 and 2021, edited by Marco Mira d’Ercole from OECD, Auke Rijpma and me (together with Joerg Baten, Conal Smith and Marcel Timmer – first report – and Mikolaj Malinowski for the second). The aim of these reports was to present the historical data to measure the various dimensions of wellbeing for the period 1820-2010, and to integrate them into one composite index of wellbeing. Global datasets of the evolution of the various dimensions of wellbeing are presented, and both reports conclude with discussing ways to estimate a composite index, based on the presented wide range of data. The odd thing about LP’s book is that he does not even mention these publications, which develop exactly the same agenda as is behind his research. In certain respects these How was Life? reports have the same limitations as LP’s book: they are first of all statistical overviews and experiments that keep the history of wellbeing at an arm’s length. And they identify ex post patterns, without presenting a thorough analysis of the ex ante driving forces of these changes. But it is strange that these publications have simply been overlooked by LP (who as a commentator was involved with at least one report).

What is missing in this literature is a theory explaining why wellbeing has changed so much over time. There is the ‘old’ story of economic growth, based on the increase in productivity made possible by the accumulation of ideas that started with the 17th century Scientific Revolution and the 18th century Enlightenment. Increases in real income then made it possible to invest more in health care, education, a clean environment etc. LP wants to distance himself from this view, rooted in growth theory. In the pages on the ‘Ultimate determinants of human development’ economic growth and technological change (other than technologies applied to better health care) are not mentioned as deep causes of the walk to freedom, and it is stressed that education and health improved also in countries that saw no rapid rise in health spending (p. 57). Is the explanation for the fact that economic growth is largely ignored as a driving force of the development of wellbeing that the author has become the victim of his own experimental calculations which he has taken for the truth? These assumptions result in a dataset in which 37% of the increase in global wellbeing is caused by the increase in life expectancy, and 32% is driven by education (p.57), leaving a meagre 31% for the rest. But rather than concluding that this is perhaps a bit too much and that his estimates may be biased, he takes this for a fact and argues that economic growth was not a driver of the process. His conclusion to chapter 2 illustrates this again: when listing the causes of human development progress he mentions ‘life expectancy was the main contributor’, ‘Education … was a steady contributor’, and ‘political and civil liberties…added substantially’ (p.64), but economic growth and technological change, the fourth subindex of the AHDI, is not mentioned at all.

In sum, via the selection of dimensions of wellbeing, the transformation and standardization of the relevant series, and their weighting, LP has created a highly subjective view of the evolution of the global standard of living in the period since 1870. The problem of subjectivity in constructing composite indices of wellbeing and in the larger wellbeing research has been receiving increasing attention. A highly convincing analysis of these links is presented in the paper by Amendola, Gabutti and Vecchi (2018), which compares various indices – including LP’s proposal – and concluded that they ‘are nothing more than a formal representation of the analyst’s ethical system’ and ‘We show how any history based on composite indices is one where both data and history play a minor role, if any.’ I think that there are ways forward in this discussion – international agreements to limit the impact of the preferences of individual scholars are probably part of the solution – but do not understand how LP can simply ignore this contribution and that of other scholars who have made similar points.

What are the policy implications? Should we conclude that countries can stop stimulating technology and economic growth, and instead focus on increased investment in health care and education – say, the Cuban model? This is not what LP writes, he does not really discuss policy implications, but it seems a logical conclusion. I think such a policy advise is dangerous for a number of reasons. There is, to begin with, no alternative (yet) for the standard explanation of the rise of wellbeing in the past 200 years being based on productivity growth made possible by the cumulative growth of knowledge. Economic growth was and is a crucial link in this story: it was and is made possible by productivity growth, but also results in the high income levels that can – via social transfers and private money flows – be transformed into better health care, or less pollution, or more personal security. Moreover, economic growth leads to higher income levels, its ‘product’ is fungible, can be transformed in whatever is required, whereas an increase in life expectancy by two years is simply that, and cannot be transformed in more education. The key phenomenon is, I would argue, not economic growth itself, the increase in per capita GDP, but the underlying growth of productivity, which simply means that we (or our machines) become smarter over time, that we can do more with less effort. Part of this getting smarter has in the past been used to lower our labour input and increase leisure – and if we prefer zero-growth or even negative growth this can be realized by working less and less hours (which also supposedly increases wellbeing). And the rest was used to increase real income.

Growth theory supplies us with a rather convincing explanation of the increase of productivity in the past 200 years, which directly and indirectly has been the main driver of the increase of wellbeing in the past. We do not have a similar theory explaining the increase of life expectancy, education, political rights, or wellbeing in general. The source of inspiration of LP’s research into wellbeing is Sen’s capabilities approach, but that is a social-philosophical framework for the conceptualization of wellbeing, not an economic historical theory about the causes of the growth of wellbeing in the past. In the slipstream of economic growth and scientific progress, life expectancy has increased dramatically, so in a way it is part of the same process explaining economic growth. But LP’s results about the enormous impact of life expectancy on wellbeing are not the result of new insights into the effect of health on economic growth – or another new feedback loop between them – they are simply based on the statistical assumptions used. Nor has the book disclosed new theoretical ideas about the link between education and wellbeing – the contribution of education to wellbeing is simply measured in a different way.

Let me conclude by repeating that multidimensional wellbeing is a important guide for the ex post assessment of the outcomes of economic development, and in that sense a valuable tool for policy review, but it is not an ideal instrument for ex ante policy advice for stepping up economic development as we lack a theory explaining it. A second conclusion might be that GDP is flawed; it has, as all concepts in the social sciences, serious limitations, but for studying long term economic change it is still better than anything else we have available (as demonstrated by LP in many pioneering papers about the construction of long time series of GDP and their analysis, most recently Prados de la Escosura and Rodríguez-Caballero 2022).

I finish with what a colleague recently wrote to me: ‘As someone from a developing country, I really just laugh at these silly debates. OF COURSE GDP is important! Income is the only thing poor people care about: sure, their lives can improve with better public services or better technology imported from abroad, but these things can make 10% of the difference whereas more income will make a 90% difference. ’

References

Amendola, Nicola, Giacomo Gabutti, Giovanni Vecchi (2018), On the use of composite indices in economic history. Lessons from Italy, 1861-2017. HHB working paper series 11. https://www.hhbproject.com/media/workingpapers/11_amendola_gabbuti_vecchi_omoQ4rV.pdf

Prados de la Escosura, Leandro, and C. Vladimir Rodríguez-Caballero (2022), War, Pandemics and Modern Economic Growth in Europe. Explorations in Economic History, available online

Stiglitz, J.E., A.. Sen and J.P. Fitoussi (2009), Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress’. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdf

Zanden, Jan Luiten van, Joerg Baten, Marco Mira d’Ercole, Auke Rijpma, Conal Smith, Marcel Timmer (eds.) (2014) How Was Life? Global Well-Being since 1820. OECD, Paris. https://www.oecd.org/wise/how-was-life-9789264214262-en.htm

Zanden, Jan Luiten van, Marco Mira d’Ercole, Mikolaj Malinowski, Auke Rijpma (eds.) (2021) How Was Life? II, Perspectives on Well-Being and Global Inequality since 1820. OECD, Paris. https://www.oecd.org/dev/how-was-life-volume-ii-3d96efc5-en.htm

Hi Jan Luiten

nice review, and useful for my students.

It would be helpful to have a PDF version to download. I have had to highlight the whole of it, paste in word and then convert into a PDF

Best

Giovanni

A not so silly debate. My response to Jan Luiten van Zanden’s “A silly debate? Leandro Prados de la Escosura’s contribution to the ‘beyond GDP’ debate”

Leandro Prados de la Escosura (Universidad Carlos III and CEPR)

Jan Luiten van Zanden has written a most negative assessment of my new book. A critical assessment means that one’s work is taken seriously and I am grateful for the time and effort it represents. However, I would like to share with you my thoughts about van Zanden’s objections hoping they may help to clarify the book’s purpose.

The book aims at presenting a historical perspective of human development in the world over the last one and a half centuries. Jan Luiten van Zanden considers the whole exercise is misleading because it is based on unwarranted and arbitrary assumptions and a complete neglect of the impact of economic growth on well-being. In my opinion, this view results from a shallow and hasty reading of the book. In the following paragraphs, I would like to argue why.

1. A subjective view of well-being?

The main argument in van Zanden’s criticism is that “via the selection of dimensions of wellbeing, the transformation and standardization of the relevant series, and their weighting, LP has created a highly subjective view of the evolution of the global standard of living in the period since 1870”.

Let me start by stressing that the approach to well-being I have followed does not start from scratch and it is not my own design but it is grounded on the theory of capabilities. This approach differs from the welfare or the income and wealth ones by placing freedom of choice at its centre. Thus, it is not simply what an individual achieves in terms of health, access to knowledge, or a decent living standard that matters from the point of view of well-being but whether she has the opportunity to choose between alternative options.

The dimensions I consider are those of the original UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI). However, I go a step further and ‘augment’ the HDI by incorporating civil and political freedoms, that is, both negative and positive dimensions of freedom. The reason why I do it is to be faithful to the theoretical concept of human development, namely, enlarging people’s choices.

Furthermore, I allow for quality as well as for quantity by transforming non-linearly (more specifically, convexly), the available indicators for a healthy life and access to knowledge, that is life expectancy at birth and years of schooling. It is not simply “the assumption … that at high levels growth is more difficult and therefore should be rewarded more than growth at low levels”, as van Zanden argues, but the need to allow for the quality changes that accompany quantity improvements what led me to introduce Kakwani’s convex transformation of the original values of life expectancy and years of schooling.

Moreover, the fact that per capita income enters the index at a declining rate (its log transformation) is because, in terms of capabilities, its return diminishes as its level rises. This makes income gains particularly relevant for human development at low-income levels, as it is the case of developing countries, and not so much for developed ones. That is why I agree with the view that economic growth matters for human development.

The omission of well-being dimensions is also pointed out by van Zanden. I accept that the AHDI is necessarily dependent on the UNDP’s HDI in its composition, so it only considers these four dimensions and, for example, biodiversity is not included. I deeply regret not having data on within-country inequality and most especially on gender inequality. However, the index includes racial discrimination and forced labour (slavery) and, at least, directly, insecurity. This is so because the liberal democracy index combines political rights and civil rights (p. 29). Thus, the ‘liberal’ component of the liberal democracy index emphasizes the importance of protecting individual and minority rights including civil liberties, the rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances. Access to justice, secure property rights, freedom from forced labour, freedom of movement, physical integrity rights, and freedom of religion are part of civil liberties.

Lastly, I would like to add that the results I obtain for the AHDI are, as I show in the book, rather similar to those derived with alternative specifications of the index, including those by Amendola, Gabbuti, and Vecchi (Vecchi, 2017) and Bértola and his collaborators, in which social dimensions (life expectancy and years of education) and the original values of per capital income are linearly transformed (not convexly) (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2 and Appendix B), so it is not just the singular features of the AHDI what determine the evolution of human development. Obviously, however, a decomposition of the AHDI progress shows that in the latter case, real GDP per capita makes a larger contribution and dominates its evolution (p. 259).

To sum up. Jan Luiten van Zanden does not like composite indices and even less the HDI, and this is fair enough. Uneasiness with composite indices is old stuff. Economists tell us that there is no economic theory behind them as in the case of GDP and, if necessary, they settle for a ‘dashboard’ of indicators. However, users and builders of indices are, more often than not, economists. A practical objection to the ‘dashboard’ is the high probability of getting opposite results when using alternative indicators, so a composite index provides a solution as a latent and elusive concept such as human development is better captured by a combination of dimensions that by each of them considered individually.

2. Should human development evolve as per capita GDP?

Apparently, van Zanden is persuaded that trends in well-being, and human development, in this case, should coincide with those of real GDP per head. I discuss extensively the issue in the book and show that even though their trends are highly coincidental in the very long run, they differ in specific phases and the first half of the twentieth century is a case in point.

He is surprised by the much more smoothed evolution of the AHDI compared to per capita income. He dramatically points out, “there are no crises, no wars, the millions who died on the battlefields and in concentration camps, have no impact on this story – there is only the smooth increase of indices, the well-paved path to freedom”. Here, perhaps, one should note that AHD dimensions are based on indicators that are, at least, in part, stock rather than flow. This accounts for its relative stability. Moreover, unlike “GDP series that are often available on an annual basis, show huge fluctuations”, data on non-income dimensions do not exist on a yearly basis so only the medium- and long-term evolution can be observed.

However, there are not only technical explanations for their different behaviour. The global diffusion of the epidemiological transition, in the case of life expectancy, and the globalisation of mass primary education took place just at the time of the economic globalisation backlash. Similar discrepancies between human development dimensions and real per capita income in other periods have an explanation in the book that van Zanden misses.

In fact, I argue through the book that divergences in the evolution of real GDP per head and the AHDI and its dimensions can be reasonably explained. Let us consider life expectancy, for instance. In a health function, in which life expectancy observations are compared to their corresponding per capita income levels, we can observe an association between them, so higher income levels match higher life expectancy. These are movements along the function. If we replicate the exercise for a period t+1 we observe a similar association but at a higher level, that is, higher life expectancy corresponds to the same levels of per capita income. This implies that there are not only movements along the health function but (outward) shifts in the function. Why is this the case? The explanation lies in advances in medical knowledge, that is, (embodied and disembodied) medical technology.

Therefore, the accusation that I largely ignore economic growth “as a driving force of the development of wellbeing” and the role played by technological change and productivity, is unwarranted. Not only I do not dismiss technology and economic growth but I find, on the contrary, that it is (medical) new knowledge and technology that allows outward shifts in the health function.

Lastly, I would like to point out that the AHDI does not show “a remarkable increase” between 1929 and 1933. The AHDI world population average hardly varies (from 0.142 to 0.144) so, given the error margin of the computation, the human lot was not better off in 1933, unlike van Zanden’s claims. It is worth stressing that the alternative augmented index that derives from the approach defended by Amendola, Gabbuti and Vecchi in Vecchi (2017) provides almost identical trends for the AHDI world population average (pp. 34-35).

3. Are relevant publications neglected in the book?

Not mentioning the publications of his research team and collaborators is one of the accusations in van Zanden’s review. This is not exactly the case. In fact, I have relied on the estimates of years of schooling provided by Clio-Infra Dataset, which underlies the education chapters of his OECD How Was Life? publications and acknowledged their authors. I did not use their life expectancy estimates because I had my own and more comprehensive ones. Moreover, liberties are not considered in the How Was Life? Publications and I did certainly, but not exclusively, draw on the Maddison Project Datasets 2013 and 2018 releases. These are the four dimensions I consider in my book. Furthermore, the book deals with composite indices, not with individual, untransformed social indicators, and Auke Rijpma’s work is referenced.

By the way, I cite and discuss Amendola, Gabutti, and Vecchi’s work throughout the book but I refer to their chapter in Vecchi’s book (2017), in which they express the same reasonings as in the unpublished working paper (which is a revised version of the chapter).

Once said all this, I would like to point out that I have been working and publishing on human development for more than a decade and even presented my results at the Utrecht seminar run by Jan Luiten van Zanden, so it surprises me too that he is surprised by my approach and findings. Perhaps this explains why I get no citations in How Was Life? Furthermore, it also surprises me that van Zanden recently co-authored a chapter in the Cambridge Economic History of the Modern World in which human development was extensively discussed given his negative view of this concept .

4. Wrong implications?

I am accused of not addressing the policy implications of the AHD findings. I accept the charge. I try to offer, as Angus Deaton nicely noted in his endorsement for the book, a historical atlas of human development and thus leave the reader to reach her own conclusions regarding policies.

Specifically, van Zanden accuses me of implicitly vindicating the Cuban model of achievements in health and education while economic growth is absent and per capita income is low and stagnant. Far from it. If anything results from my approach to human development is that the suppression of freedom and agency is incompatible with it. This explains the collapse of the human development index in the case of Cuba and other totalitarian regimes.

5. Is this a silly debate?

van Zanden’s critique could be summarised in his question, “Is the explanation for the fact that economic growth is largely ignored as a driving force of the development of wellbeing that the author has become the victim of his own experimental calculations which he has taken for the truth?”. In both cases, my answer is no. I do not ignore the role of economic growth and I am not a victim of delusion. I simply try to widen the view of well-being using a capabilities perspective. This approach does not ignore the importance of growth but evidence that different levels of human development can be achieved at the same level of per capita GDP.

To sum up, my answer to Jan Luiten van Zanden’s initial question is no, this is not a silly debate on well-being but a most relevant one that deserves to be pursued.

The use of composite indices in economic history: A long-standing, not silly debate

Nicola Amendola (U. of Rome “Tor Vergata”)

Giacomo Gabbuti (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna di Pisa)

Giovanni Vecchi (U. of Rome “Tor Vergata”)

In the interesting debate on the use of the HDI in economic history hosted by this blog our work has been quoted in a number of circumstances. Jan Luiten van Zanden refers to our working paper (Amendola, Gabbuti and Vecchi, 2018) in support of his criticism on the subjective nature of the HDI. Leandro Prados de la Escosura refers to our book chapter (Amendola, Gabbuti and Vecchi, 2017) arguing that it provides a sort of sensitivity analysis exercise with respect to his results related to the Kakwani’s (1993) transformation. We thought it would be useful to clarify a few points.

Leandro Prados de la Escosura correctly identifies our contribution in the book chapter as a constructive one. In Amendola, Gabbuti and Vecchi (2017) we focus on Italy between 1861 and 2011 and explore the use of the HDI by including the dimensions of political and civil rights, and investigate how the convex (Kakwani’s) or concave (original HDI proposers’) transformation affects 1) the dynamic of the HDI and, 2) the marginal rates of substitutions (MRS) among its components (the troubling trade-offs identified by Ravallion, 2012). The paper concludes that “the HDI largely reflects the preferences of its creators. If the person who uses it is a historian, then the HDI will largely reflect his/her own judgment of history.” Within this framework, and after calculating Prados de la Escosura HDI’s implicit MRS (Box 2 on pages 471-72 in Amendola Gabbuti and Vecchi 2017), we advised against convex transformations. That is in line with van Zanden’s argument in this blog.

Our 2018 working paper is more than a revised version of the book chapter. In Amendola, Gabbuti and Vecchi (2018), we adopt a different perspective, and focus explicitly on the interpretative limits of the HDI in economic history. The main point of the paper is that the HDI can be interpreted not only as a social welfare function (SWF), as also observed by Fleurbaey (2018), but as a paternalistic SWF (Graaf, 1957), and this has two main implications. First, the choice of the indicators (GDP, life expectancy at birth, etc.) and the choice of the aggregation rule (which formula to pick for the HDI) is a purely subjective decision of the analyst. This is uncontroversial, it has been mentioned by van Zanden, and acknowledged by Prados de la Escosura. The second implication is more subtle, and goes way beyond the arbitrariness of the choice of the variables and/or of the weighting system. To establish that the HDI is a paternalistic SWF implies that HDI is a welfare measure totally disconnected from individual preferences. In other words, the HDI cannot be derived by aggregating individuals’ utilities (or well-being measures), unless one imposes on individuals the same preferences of the analyst (Foster, and Shneyerov, 2000), and that is another way of saying that HDI is a paternalistic SWF that induces an arbitrary ordering over a set of social indicators.

To clarify this point further, in the paper we introduce a formula of the HDI based on a constant elasticity of scale (CES) function. As we know, the CES function is governed by a single parameter determining the extent to which different variables (here the HDI dimensions) can be substituted one for another: in the present context, the CES function is applied to the HDI (or to any of its ‘augmented’ versions) and the elasticity parameter controls the extent to which GDP and life expectancy, say, are substitutes, and this applies to any pair of its dimensions (education, political and civil rights, etc.). This CES-parameter is not “old stuff”: it has nothing to do with the choice of the dimensions entering the HDI (which is still well worth of discussion), nor does it relate to the choice of the weight that each dimension receives within the HDI. The choice of the elasticity of substitution uniquely determines a specific formula of the HDI, and is driven simply and solely by the ethical system of the historian. In this sense, the choice of the CES parameter (i.e., of the specific HDI) tells you about the pater of the HDI, that is, it reveals his/her preferences on the trade-offs that necessarily come by composing different standard of living indicators into a single measure.

The flexibility of the CES function allows us to come up with an encompassing formula that embeds all the HDI formulae proposed in the literature. We show that if the elasticity of substitution is assumed to be infinite (i.e., the variables defining the HDI are perfect substitutes), then we obtain the HDI originally proposed by the United Nations Development Programme. If the elasticity of substitution is set equal to 1 (imperfect substitution), then we obtain the so called ‘hybrid HDI’ (Felice and Vasta, 2015). And so on. We use Italy as a case study to illustrate the ultimate consequence of the paternalistic nature of the HDI: by changing the elasticity of substitution parameter (but not the weighting system or any other choice underlying the calculation of the HDI), it is possible to obtain very different temporal trajectories for the HDI. In short, with the HDI anything goes.

Prados de la Escosura observes that the risk of adopting a “dashboard approach” is represented by “the high probability of getting opposite results when using alternative indicators, so a composite index provides a solution as a latent and elusive concept such as human development is better captured by a combination of dimensions that by each of them considered individually” In this perspective, the case of Italy is paradigmatic. During the “Fascist ventennio” civil and political rights go in the opposite direction with respect to the other indicators. The pars construens of our paper can be summarized as follows: the use of HDI in economic history is a solution (in the sense indicated by Prados de la Escosura) if and only if we can pick a specific value (or a subset of values) for the elasticity of substitution, and agree on sticking to it: does the economic historian have a way to support his preference for a zero elasticity versus an infinite elasticity, or any value in between? Can he persuade other scholars about the use of convex transformations? Perhaps. Not in the short term, as far as we can judge from the current academic debate, but it is a possibility that should not be ruled out.

We argue that the real question for this debate is whether it is preferable, in historical analysis, to discuss about a restriction of a parametric space (which value should we use for the elasticity of substitution of the HDI components?), or to deal with the complex, non-ergodic, often conflicting relationship among well-being dimensions using a more traditional approach where multidimensionality is not squeezed to a scalar in a paternalistic way. All this makes the debate initiated in this blog a most important and welcome one.

References

Amendola, N., G. Gabbuti and G. Vecchi (2017), “Human Development”, in G. Vecchi, Measuring Wellbeing. A History of Italian Living Standards. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 454-491.

Amendola, N., G. Gabbuti and G. Vecchi (2018), “On the Use of Composite Indices in Economic History. Lessons from Italy 1861-2017”, HHB Working Paper Series n.11

Felice, E. and M. Vasta (2015), “Passive Modernization? Social Indicators and Human Development in Italy’s Regions (1871-2009)”, European Review of Economic History, 19(1): 44-66.

Fleurbaey, M. (2018), “On human development indicators”, UNDP Discussion Paper.

Foster, J. E. and A. A. Shneyerov (2000), “Path Independent Inequality Measures”, Journal of Economic Theory, 91(2): 199–222.

Graaff, J. de V. (1957), Theoretical Welfare Economics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kakwani, N. (1993), “Performance in Living Standards. An International Comparison”, Journal of Development Economics, 41: 307-336.

Ravallion, M. (2012), “Troubling Tradeoffs in the Human Development Index”, Journal of Development Economics, 99(2): 201-209.

From subjectivity to inter-subjective standards?

Jan Luiten van Zanden, Utrecht University

Thanks for the illuminating contributions to this debate. Let me start by clarifying that I am not against composite indices of wellbeing – on the contrary, I have devoted much time and energy to experiment with this idea. My main concern is that we should move into the direction of common standards for this kind of work, that we should develop a common framework for the construction and analysis of such composite indices, instead of constructing our own particular indices for our own particular project. In the two volumes of How was Life? we tried to suggest certain standards to which I return below, but clearly this has not had the impact we hoped for. We did not anticipate the contribution by Amendola et.al., restated in their note on composite indices to this debate, that the degree to which dimensions of wellbeing are substitutes of each other, and that this implies that the ‘production’ of wellbeing can be conceptualized as CES production function, which in a way further complicates but also clarifies the problems that we face.

One way of looking at this debate is to compare it with the debate in the 1940s and 1950s about how to conceptualize and measure GDP. Economic theory could only to a very limited degree guide the choices that had to be made, for example about the question whether the manufacture of arms should be considered a contribution to national income or not (Kuznets defended the latter position, but his view was discarded). Welfare economics was the ‘natural’ home to the ‘new’ concept – which was used to measure the welfare of nations – but the concept that emerged, national income, was only very distantly related to mainstream welfare economics (the latter measured welfare as the consumer surplus, whereas national income was measured as the actual output/value added of the products concerned). Yet, despite the weak theoretical foundation of the concept and the actual measurement of national income, it became a huge success, partly because the experts managed to create a common framework for estimating it, partly because it fitted economic and political realities of the period, and partly because it was a very convenient measure (one could compare almost everything – consumption, investment, government spending with national income).

The popularity of the wellbeing debate shows that this concept also fits contemporary economic and political realities in (some of the) rich countries (it has for example become very trendy in the Netherlands). But possible success is undermined, in my view, by the fact that it is a very abstract concept, difficult to comprehend and to visualize – but perhaps creative minds can do something about this. The real problem, however, is the lack of consensus about how to measure it, leading to a proliferation of scholarly work based on – we all agree – subjective choices of wellbeing dimensions, weights, transformations and degrees of substitution between dimensions. The ‘degrees of freedom’ in this research area are huge, which will make it very difficult for an author or a teams of authors to set a standard that will be accepted by all involved. In the How was Life? reports we tried to propose a certain standard, building on the OEDCD how is life? project, and making use of large historical datasets that were collected for this purpose. We, in fact Auke Rijpma, the author of the two concluding chapters, used factor analysis to trace common patterns and to analyse the evolution of a underlying latent variable, which was assumed to represent wellbeing. Much can be said about this – it is certainly not the final solution for the choice of weights – but it shows that smart econometrics may help to address some of the problems. The other step that we can take is even more important: to start an open discussion about the standards of this kind of economic historical research. Does it make sense to follow the OECD guidelines? Which dimensions of wellbeing are most relevant and can be measured in the long-term? The list of questions is long, and it is unclear how consensus can be reached. Perhaps the model of the Maddison Project, which plays this role for historical national accounting, can be adopted. A common standard can perhaps convince scholars that this is the best way forward, as it will help to make this academic work more comparable in time and space. Subjectivity will hopefully be succeeded by intersubjectivity – and perhaps smart econometrics making use of the vast historical datasets that are at our disposal may even make it possible to test certain assumptions (for example, related to the Kakwani transformation). I am happy to help organize such an initiative.

From subjectivity to inter-subjectivity? Not quite so!

Leandro Prados de la Escosura

Thanks for your reply. Let me answer point by point.

1) You claim not to be against composite indices of well-being. However, this is not what transpires from your text.

2) You propose to move away from particular subjective indices towards a common framework. Fair enough, but I reject my work’s depiction as ad hoc and subjective. As I tried to explain in my reply, my work builds on the capabilities approach to well-being that depicts human development as enlarging people’s choices. This is one of the possible way to address well-being as the utility (welfare) or the opulence (income) approaches are (Sen, 1984).

3) As you insist on Amendola et al. contribution, perhaps you should acknowledge that they are simply against composite indices. Read your quote from their paper again: ‘any history based on composite indices is one where both data and history play a minor role, if any’.

4) Your description of GDP as a weakly founded concept only distantly related to welfare economics ironically places it, together with the HDI (and Auke Rijpma’s welfare index derived using factor analysis), in Ravallion’s ‘mashup’ indices’ waste bin.

5) You refer to GDP as a ‘very convenient measure’. This was exactly the purpose of the HDI. As Amartya Sen (2020) put it, its purpose was ‘to compete with the GDP with another single number—that of human development—which would be no less vulgar than the GDP, but would contain more relevant information than the GDP managed to do’.

6) You say the well-being debate is undermined because it is a ‘very abstract concept’. I would add that well-being could be depicted as a ‘latent’ variable and that is why a composite index such as the Augmented Human Development Index may provide a solution.

7) There is no lack of consensus about how to measure well-being, but there are different approaches. I would like to remind that the HDI is already 30 years old and remains widely used unlike many other attempts to provide a synthetic index of well-being over the last 70 years (Klasen, 2018). This means that it has been accepted by many, including scholars. Obviously not everybody does like it, but this also happens with GDP as a measure of well-being.

8) Your use ‘subjective’ in a very loose. There is nothing more subjective in the capabilities approach than in the welfare approach to well-being.

9) Let us resume our conversation about the assessment of well-being. Surely different cognitive perspectives will help to improve it.

References

Gallardo-Albarrán, D. (2019), “Missed Opportunities? Human Welfare in Western Europe and the United States, 1913–1950”, Explorations in Economic History 72: 57–73.

Klasen, S. (2018), Human Development Indices and Indicators: A Critical Evaluation, 2018 UNDP Human Development Report Office Background Paper.

Sen, A. (1984), “The Living Standard”, Oxford Economic Papers 36: 74-90

Sen, A. (2020), “Human development and Mahbub ul Haq”, Human Development Report, The Next Frontier. Human Development and the Anthropocene, New York: United Nations Development Programme, p. xi.